Workers’ pressure to tie wage increases to inflation unsettles central banks

Some workers in Europe and South America are increasingly successful in securing deals that tie wages and inflation.

Tying people’s wages to inflation is much less common than it was in the 1970s when it became widespread in some economies, including the US and the UK. However, there are signs of a resurgence in countries such as Spain and Brazil.

Claudio Borio, head of the financial and economic division at the Bank for International Settlements, often called the central bank’s bank, said inflation made it harder for inflation to shift by distorting market signals.

“The decision will not be the right one,” Borio said. “With indexing [inflation] Embedded, that’s what happens [automatically]”

In Spain, with annual inflation of 10.5% in August and electricity prices rising 70% over the same period, unions win negotiations to make members’ contracts more price-linked .

Such contracts already cover almost a third of Spain’s collective wage agreements, according to the central bank, less than a fifth at the end of 2021 and expected to reach half next year. I’m here.

Pablo Hernández de Cos, Governor of the Bank of Spain warned Earlier this year, the risk of a dreaded ‘wage-price feedback loop’, where inflation would become harder for central banks to control, further increasing wage pressures.

UGT, one of Spain’s largest unions with 960,000 members, defended the deal, saying workers should not “pay the price of the crisis again”.

So far, like most European workers, wages in Spain are well below inflation. Spanish bank CaixaBank built a wage tracker based on client payslips and showed that he had risen 2.5% in the year to June, up from 2.4% in May.

However, figures released on Thursday by Eurostat, the European Commission’s statistical office, showed that hourly wages in the eurozone rose by 4.1% in the second quarter of 2022 compared to the same quarter last year. . The strongest surge in at least a decade surprised economists who expected wage growth to fall from 3.3% in the first quarter to 1.8% in the three months to June.

A continuation of strong wage growth and an upward trend in prices could raise concerns for this generation of monetary policymakers.

Earlier this year, the European Central Bank rejected calls from workers’ unions for inflation-linked wage increases, but at its meeting in July, it discussed signs of more widespread price increases.

Some countries, including Eurozone member states such as Luxembourg, Cyprus, Malta and Belgium, have never completely eliminated indexing. But Luxembourg this year stopped wage hikes under indexation rules and instead gave workers tax credits.

In Belgium, there is growing debate over a rule that would automatically adjust the wages of most public and private sector workers to a “healthy index” of inflation that excludes fuel, alcohol and tobacco prices.

The rule means that hourly wages in Belgium will rise by a total of 12% over the next two years, the country’s central bank said. weatheris 4.8 points higher than France, Germany and the Netherlands, where price indexation is less common.

National Unizo Users Association Said Wage increases at that level would be “disastrous for the economy and jobs” and called for an “index skip” by the government to bring down expected wage increases for this year.

The idea was rejected by Lars Vande Keybus, economic adviser to ABVV, Belgium’s largest trade union with 1.5 million members. “Purchasing power is very important if we don’t want to end up in a deeper recession next year,” he said.

This practice also provides a means of protecting the most vulnerable from cost of living crises. In many economies, minimum wages and pensions have long been price-linked.

But in Brazil and Argentina, economists say the practice is becoming increasingly important as the reason the recent spike in inflation has taken hold.

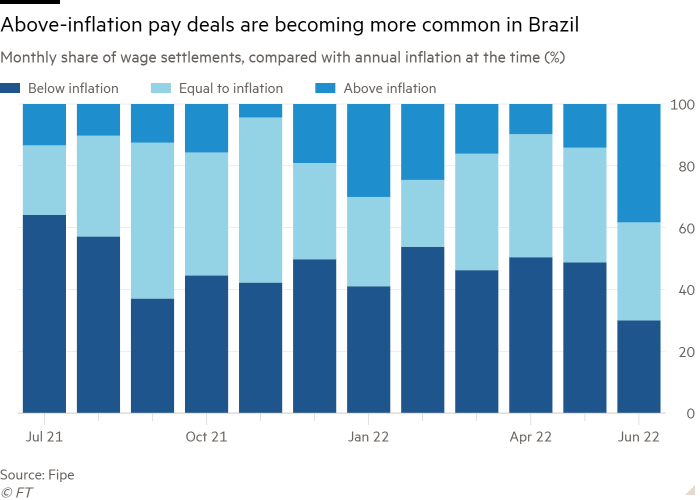

After years of having to settle for modest wage increases, more than 70% of the raises given to Brazilian workers in June were more than the rate of increase in consumer prices.

Economist Alessandra Ribeiro of Sao Paulo consultancy Tendências said that through 2019, 32-35% of inflation was due to inflation. Today it is 40%, she said, adding: It is very difficult for central banks to control inflation. ”

Brazil’s minimum wage was raised by 10% late last year in line with rising prices.

In neighboring Argentina where inflation is progressing Be expected Indexing is also taking hold as it hits 90% this year, extending to private healthcare spending this year.

Soaring prices have replaced annual payment rounds with semi-annual and even quarterly negotiations in Argentina. “Shock spreads faster [encouraged by indexation] Santiago Manoukian, chief economist at Buenos Aires consultancy EcoLatina, said it could lead to a series of bad outcomes.

https://www.ft.com/content/3af9cfb0-df3d-4e64-9411-7747515577df Workers’ pressure to tie wage increases to inflation unsettles central banks