Hunt returns to ‘fiscal orthodoxy’ in the face of tough financial times

Rarely has a prime minister been faced with a terrifying array of economic forecast drafts by the UK’s financial watchdog, such as those presented to Jeremy Hunt over the past few weeks.

But unlike his predecessor, Kwasi Kwarteng, Hunt willingly accepted the dire economic and financial forecasts put forward by the Office of Budget Responsibility and acted decisively in response.

He used the autumn statement to £55bn annual fiscal consolidation iaccompanied by significant public spending cuts and tax increases.

“With just under half of the £55bn consolidation coming from taxes and just over half coming from spending, this is a balanced plan for stability,” Hunt told the House of Commons.

He blamed Kwarten and his ‘mini’ budget for causing turmoil in financial markets by failing to contain £45bn of underfunded tax cuts and picking up a series of OBR projections.

“Tax cuts without money are just as dangerous as spending without money, so we quickly withdrew the planned measures,” Hunt said.

Callum Pickering, an economist at Berenberg Bank, said the fall statement signaled a “return of fiscal legitimacy.”

The big problem underlying Hunt is that not only did OBR predict that the UK economy was already in recession, The five-year outlook was also significantly weakened.

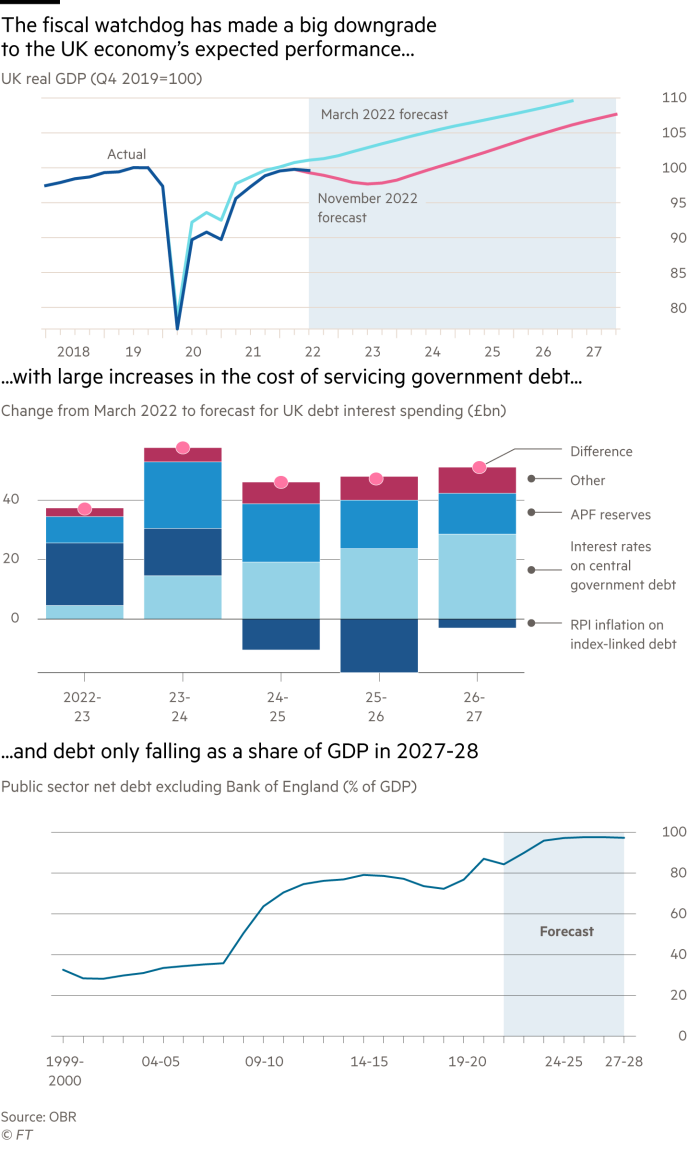

We forecast no economic growth at all across this Congress from late 2019 to late 2024. Cumulative growth from 2019 to 2027 was 3.4 percentage points lower than the OBR forecast in March.

Weak outlook primarily reflects downgrades to historical data reflecting weaker performance during the Covid pandemic, OBR’s view that the economy is currently overheating, and a downgrade in its assessment of future growth potential. I’m here.

This has resulted in a very weak medium-term fiscal outlook.

With interest rates expected to continue rising over the long term, the OBR has significantly raised its projections for the cost of servicing government debt. This added him £52bn to public borrowing next year, equivalent to about 2% of national income, and increased the budget deficit for 2026-27 by £46.6bn.

in the meantime, Increase in national pension and welfare benefits Higher inflation would have the effect of raising the expected cost of such support, as the bill would be permanently more expensive for the government.

Putting these effects together, Mr Hunt was presented with OBR’s fiscal projections for the past few weeks, showing government borrowing to balloon to £106.4bn over 2026-27. In his March forecast alongside the spring statement, OBR had calculated a deficit of just £31.6 billion for the year.

Martin Beck, economic adviser to forecasting firm EY Item Club, said the OBR’s ‘poor prognosis for the economic outlook’ has left the financial forecasts ‘fact’.[ing] accompanied by a significant upward revision of public borrowings exceeding . . five years.”

With the underlying finances cut so sharply, OBR told Hunt ahead of its fall statement that it is unlikely to fit into any of the government’s existing fiscal rules. The main rule was that debt as a percentage of gross domestic product should fall by the third year of the OBR projection.

Hunt’s response was to create new fiscal rules that included a reduction in the debt share of gross domestic product by the fifth year of the OBR projection.

Capital Economics economist Paul Dales said Hunt had “relaxed” the rules, making them easier to attack.

But even with the rule change, Mr. Hunt could not show that the rule was passed without significant spending cuts and tax increases. If the Prime Minister does nothing, the OBR will see government debt still rising as a percentage of his GDP in 2027-28, his fifth and final year of the Fiscal Oversight Agency’s projections. I calculated that

Some economists wanted Mr. Hunt to loosen fiscal rules further, rather than squeeze spending and raise taxes.

Haley Law, an economist at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, a think-tank, said the “small” budget debacle meant that “the prime minister will not be able to achieve arbitrary fiscal targets amid the headwinds the economy is facing.” We have been forced to unleash the fiscal contraction hastily,” he said.

Hunt disagreed. He chewed the bullet and tried to close the fiscal gap by introducing £55 billion in spending cuts and tax increases. Daily spending on public services and capital investments has been significantly reduced.

However, the overall budget tightening was less severe than before, as Hunt’s measures offset net tax cuts and increased spending from several government statements and emergency interventions since the March spring statement.

The timing of Hunt’s measures varies markedly. Spending cuts of £30bn a year will be postponed until the recession is expected to end. The government is poised to support the economy next year by capping household utility bills and providing additional funding for schools and hospitals.

tax increase is coming soon, However, a £7bn revenue-boosting measure was implemented in April and has steadily increased since, raising £25bn a year by 2027-28.

Even when Hunt announced the biggest budget cuts since 2010, the OBR said it had been less careful than the former prime minister in building fiscal resilience.

Ultimately, after £55bn of spending cuts and tax increases, the Fiscal Commission decided Mr Hunt was likely to meet the new budget rules.

“This prime minister leaves relatively little headroom for the new fiscal targets he has proposed compared to previous prime ministers,” OBR said.

But it was enough to show the return of economic legitimacy to 11 Downing Street after the ill-fated premiership of Liz Truss, and the market’s response to the autumn statement was lukewarm.

Governments use fiscal policy to support the economy through a recession and then tighten their finances. And it imposes hard enough fiscal measures up front to show the market that it’s serious about spending cuts and tax increases.

https://www.ft.com/content/5608695a-ae0a-49bd-834e-78b473f754fd Hunt returns to ‘fiscal orthodoxy’ in the face of tough financial times